Continued from Part 1. Reader Beware, spoilers abound!

A Paradigm Shift

The mission to retrieve the “precious natural resource” leads to a series of fantastic events involving ostrich riding, the staging of a thespian play, an adrenalin-pumping chase, and the wrongful arrest and imprisonment of a trio of prairie dogs. It is a key sequence in Rango’s story, and like the rest of the film it is filled with symbolic and verbal allusions to it. After the group follows a tunnel of pipes to its end, Mr Furgus announces, “It’s the end of the line.” But in the search for yourself, as we will soon see, an apparent dead-end, a point of resignation, is critical to making the need transition. Also, Elgin wonders why they’re talking about finding water, “I thought we were following bank robbers.” Remember, he is right. Rango at this point never intends to actually find the water. And we’re not sure he’s even trying to find the robbers. He’s trying to look busy trying. So it is very on the money when another member of the posse Turley responds, “we are experiencing a paradigm shift.” It is true. The story is shifting from a question of where the robbers are, to where all the water went, and even bigger than Turley realises, to what sort of leader they had chosen for themselves.

The chase is ultimately futile, and they return to Dirt with Pappy and his boys as prisoners, but with no water. The town is Dejected. Rango’s lies catch up with him when Rattlesnake Jake shows up, summoned by the Mayor after he is accused of stealing the water by Rango. In a tense dialogue, Rango is upbraided by Rattlesnake Jake who has our hero wrapped in a tight coil. He dares Rango to shoot him. “You got killer in your eyes, son? I don’t see it.” He gets Rango to confess to the lies that got him there.

In the saloon, Rango saw himself as a dreamer. Now, Rattlesnake Jake exposes him as a fake. Rango is forced to admit this in the coils of Rattlesnake Jake. What the serpent offered, unbeknownst to him, was an intervention. And how symbolic that both Rango’s enemies, the turtle Mayor and the serpent enforcer, are symbols of cunning and wisdom in many folklore traditions, including in the Christian scriptures, where the serpent is an ultimate symbol of subversive wisdom and deceit.

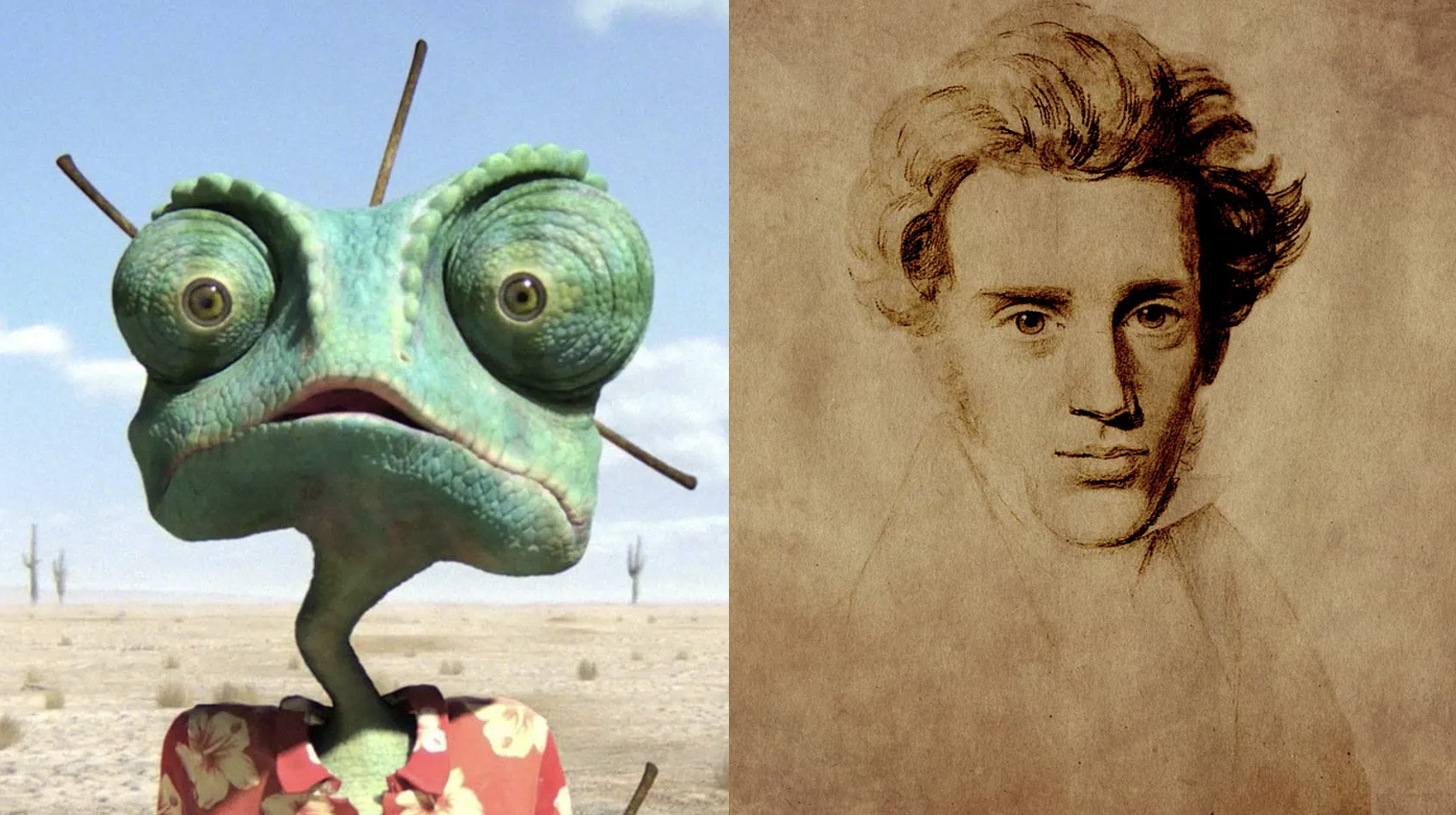

But as Roadkill hinted, the desert is also a place of truth. It has shown him the truth: Dirt is ruled by a corrupt turtle and a ruthless rattlesnake. As Rango ambles dejected through it, he experiences the intensivity, the ultimate solitude, that Kierkegaard says is necessary on the journey to yourself. He has time to think about everything that is happened, to feel it all, to process it. He has already admitted his is a fake. Now he must accept it. This leads to the most intense form of despair.

“I am Nobody,” Said the Knight of Infinite Resignation

After his humiliating encounter with the snake, the dejected chameleon makes a harrowing walk back into the lonely desert. His trek takes him over dunes and to a road, which he crosses mindlessly as cars whizz by in the night. Rango is at a point in his journey Kierkegaard calls infinite despair. “Who am I?” he asks again. “I am nobody. One gets the sense, assisted by Hans Zimmer’s melancholic music, that the lizard is suicidal, or at least indifferent about his safety. It is a tension between two true realisations. The individual sees herself for what she truly is, in an even more intense sense than I described before. The individual also sees the true future she faces if is to move up the religious stage. She sees that it is not a bed of roses.

A key emotion at the junction between the ethical and the religious is guilt. They become acutely aware of their faults, in Kierkegaard’s Christian wording, their sin. As Lydia Amir puts it, “Consciousness of these facts and the contradictions they entail results in resignation, a dying to the world, which culminates in complete renunciation” of reality.[9] This is what happens to Rango when he walks into traffic. He is resigned to the reality of who he is. “I am nobody.” This self-resignation is essential to Kierkegaard’s philosophy. Lydia Amir calls it self-annihilation, and that is certainly what Rango looks like he is going through in this scene.[10] The one who reaches this point, defeated by the weight of the truth of who they really are, and who realises the futility of attaining what they really want, is called the knight of infinite resignation. Alistair Hannay puts it well: “There is no faith, in Kierkegaard’s sense, without prior resignation… and there is no resignation unless there is something in the world that a person wants in the strong sense in which one says he or she has set his or her heart on it.”[11] Each person must find the truth they are willing to live and die for.

Rango, Knight of Faith

Infinite resignation occurs in the encounter with the Absolute, or God. After he has crossed the road, Rango falls unconscious and is carried to safety by a carpet of pill bugs. When he wakes up, he realises he is in the presence of the Spirit of the West, who looks like a middle aged white male tramp. We are met immediately with another poetic allusion, “Ah, there’s a beaut. Sometimes you gotta dig deep to find what you’re looking for. So you made it.” The statement is ostensibly in reference to the fish hook he has just found in the sand. But it also refers simultaneously to the soul searching our hero has just done, and to the Herculian effort that awaits him if he is to complete his transformation.

The dialogue they have is utterly fascinating and patently Kierkegaardian in its philosophy.

Rango: What are you doing out here?

Spirit of The West: Searching. Same as you.

Rango: I don’t even know what I’m looking for anymore. I don’t even know who I am… They used to call you ‘the man with no name.’

Spirit of The West: These days they got a name for just about everything … it doesn’t matter what they call you; it’s the deeds make the man.

The dialogue produces a line of thought I will explore later in an optional aside. For now, Rango’s encounter with the Spirit of the West expresses the knight of resignation’s encounter with divinity. It is not an encounter that makes immediate sense. Divinity represents something intangible to our sensory experience but nonetheless real. It is a strangeness, not the glorious theophany we would expect. Rango certainly did not expect to find a bum searching through the sand for rusty old metals. His alabaster chariot is a golf cart. His golden guardians are four golden Oscar figurines “shining in the sun.”[12] So this spiritual encounter is by no means an easy one to believe. In fact, it is positively absurd. It may be surreal in the moment, ineffable after it has ended. But was it real? Can it be trusted? Rango has a choice to make.

Because the encounter does not conform to our ordinary human expectations, trusting it can only amount to an act of faith. This is the leap of faith. The leap of faith is connected to another famous saying from Kierkegaard, “life is lived forwards and understood backwards.” What does he mean? Life is full of endless possibilities. This creates a dizziness of freedom that can be paralysing. Most people experience this. It contributes to a social condition he calls reflection, which we will come back to in an optional aside. In the multitude of options it is not possible to objectively know what the best path to take in life is. This level of freedom is overwhelming. It grounds a state Kierkegaard calls anxiety. He does not mean it in the psychological sense strictly. Rather, in a philosophical (ontological) sense he means that humans exist naturally in a suspension of unsettled options. In fact, that analogy from chemistry is helpful. You can think of anxiety as the human version of a suspension.

Anxiety is not a feeling, it is a state of being, and it is natural. But it can produce feelings of anxiety in the psychological sense, so he distinguishes between conscious and unconscious forms. The lizard is a quintessential demonstration of this. He is consciously plagued by his inability to settle on a version of his personal identity that he can experience as his true being. At the same time, unconscious to him, as the movie so beautifully unfolds, he exists in a suspended state of infinite potential.

Kierkegaard often calls the leap of faith “acting on the strength of the absurd.” The encounter with divinity is inherently absurd since the absolute does not conform to anything in the world. But it has a compelling pull on the pilgrim of selfhood: “on this the knight of faith is just as clear: all that can save him is the absurd; and this he grasps by faith.”[13] Rango now has the idea for which he is willing to live and die. And he returns to Dirt with nothing more than a conviction. He is no smarter, no stronger, no richer. He is only surer. On arriving, he is quizzed by Maybelle. “You got a lot of nerve showing up here, lawman. What is it you want?” His reply is worthy of every goosepimple. “Your Papi and them boys about to hang for something they didn’t do. But I’ve got a plan.”

A Truth To Live and Die For

This level of conviction, this faith in himself and his plan, is based on enlightenment. After his encounter with the Spirit of the West, Rango is shown the mayor’s plot to divert water from Dirt into the desert to build the future. The wise armadillo has come back to grant the promised enlightenment, helped by a more purposeful posse, comprised of walking cacti. They take him up a hill to the edge of the desert, and show him the lush, modern city the mayor is building. It is almost a parody of Moses taken atop Mount Pisgah by the Lord so he could see the promised land. Once again, the writer puts Rango on the spot. The Roadkill asks him, “what now, amigo?” Rango does not rush to some flippant answer. He does not flippantly scream “We ride!” He is considered. He paces to the edge of the hill and looks out into the distance at the road that brought him here. As he gazes out onto it, cars pass by, the contraptions that flung him into this whole story, that catapulted him unexpectedly into conflict.

The road represents the possibility of retreat, going back to the old life of shallow pretence, the life of meaninglessness, boredom, daydreaming, and lostness. It represents a point of decision, a line in the sand. Is Rango still, as was put to him in the saloon, “a long way from home?” or was he already home? As Kierkegaard would have it, destiny is fashioned not by moving away, but by facing life right where you are. “Becoming,” he concedes, might involve “a movement from some place, but becoming oneself is a movement at that place.”[14]

The road represents, in a word, despair. Despair instigates the movement from the aesthetic to the ethical, and from the ethical to the religious phase. It is brought on by intense conflict. Despair is what Abraham faced when YHWH commanded him to slay his son Isaac.[15] It is what Jesus faced in the garden of Gethsemane before his final arrest. It is what happens to the hero of a story when she experiences her ‘dark night of the soul’ before emerging transformed and ready to take on the villain(s). Despair happens at a junction of the journey to selfhood. It marks a choice between what you are and what you can be. For Abraham, a wandering warlord, or the father of nations; for Jesus, a good teacher or the saviour of humankind; for Rango, a lost pet or the saviour of Dirt?

Rango, our knight of infinite resignation, realises he cannot turn his back on Dirt. And so, as Kierkegaard says,

“the knight makes the movement, but what movement? Does he want to forget the whole thing?… No! for the knight does not contradict himself, and it is a contradiction to forget the whole of one’s life’s content and still be the same.”[16]

Rango realises he would be denying his own reality if he walked away. If he did so, he would become what Kierkegaard calls the tragic hero, who makes the movement of infinite resignation, but instead of proceeding onwards, returns to the safety of the universal. The universal is the aesthetic and the ethical spheres, and the infinitude that comes with it. But Rango does proceed. “No man can walk out on his own story,” he declares. Ironically, it is Roadkill, the armadillo who helped bring him to this realisation who asks, “But why?” The question is almost a test of transformation. “Because that’s who I am.” Rango has arrived. He has made the movement, as the Danish philosopher likes to put it, and graduated from being the knight of resignation to the knight of faith, aka the single individual. The knight of faith does not give up on their earlier hopes. They simply realise that this hope defines them. And they own this hope as a point of vulnerability. There is no hiding from the Absolute. In this sense, Kierkegaard says, “faith is: that the self in being itself and in willing to be itself rests transparently in God.”[17]

Without such a hope, Kierkegaard says, no-one can reach this point and make this movement, “For the knight will then, in the first place, have the strength to concentrate the whole of his life’s content and the meaning of reality in a single wish.”[18] In his Journals and Papers, he puts it another famous way, “the crucial thing is to find a truth which is truth for me, to find the idea for which I am willing to live and die.”[19] Without such a truth, one “will never come to make the movement.”[20] Rather, Kierkegaard says, that person will live a prudent life, like a capitalist who diversifies her investment portfolio so she can ensure a net gain. But they will never transcend the mundane existence of the aesthetic-ethical life. They will remain society’s person, a “mass man.” But if one does make the movement, they will find that enlightenment on the journey to their true self is not the discovery of some new truth, some higher principle. It is simply the realisation of the sacredness of a truth they have already held dear. And they will find that the movement into selfhood is really a return to who they have always been. Faith does not earn one a new blessing; it receives the old desire as a blessing. This is why Kierkegaard calls the whole process of movements from aesthetic to religious existence repetition.

But faith, for Kierkegaard, is not simply a conviction or a belief. It is a paradoxical existence: faith is precisely the paradox that the single individual as the single individual is higher than the universal, is justified before it, not as inferior to it but as superior… the single individual stands in an absolute relation to the absolute.[21] This means the single individual, or the knight of faith, returns to the universal, the world of rules and pleasure, to live above it. The knight of faith transcends, upends, and demolishes the structures of reason that uphold the moral edifice of society. This is another reason his philosophy is so extendible beyond provincially Christian concerns. It applies to the believer, the religious practitioner, and atheist alike. Once one finds with certainty that limiting ideal outside of oneself, and outside of the ordinary rubric of order provided by society, the state, religion, the Internet, or whatever other institutions we are beholden to, one is ready to face the world again. The concept is central to many religious and philosophical traditions. Yet, making the return is not necessarily easy to do, as Rango was to find out. Sometimes you have to face off with a Rattlesnake called Jake.

The next two sections are not precisely on topic and can be skipped without missing the argument. Don’t miss the conclusion, though.

Aside 1: Reflection in The Present Age

Returning to the dialogue Rango has with the Spirit of the West, philosophers have long debated whether human beings are born with selves that remain the same throughout their lives (essentialism) or whether we become who we are as we experience life (existentialism). Some of the existentialists have also debated whether the process of becoming a self is dictated by the society (communitarianism) or controlled by the individual herself (individualism). Kierkegaard, of course, is seen by many as the father of the existentialist school, but there is still raging debate on whether he is an individualist or communitarianist. Recently, agreement is emerging that he sits somewhere between, as a proponent of relationality. The Spirit of the West’s assertion that “it doesn’t matter what they call you” firmly rejects essentialism. His pronouncement that “it’s the deeds make the man” affirms the existentialist approach.

But his assertion that “these days they got a name for just about everything” raises Kierkegaard’s concern that the present age is characterised by an obsession with intellectualism. Everything is discussed, everything is labelled, everything is classified, but nothing is done. This is an age that has replaced action with what he calls reflection. In his book Two Ages, he says, “Our age is essentially one of understanding and reflection, without passion, momentarily bursting into enthusiasm, and shrewdly relapsing into repose.”[22] People will even pretend to do things by discussing the need to do them, or how they will go about it. Kierkegaard is not against thinking and discussion. Rather, reflection is “an ethos, or group spirit, or social inertia, in which this stagnation becomes accepted as normal and normative.”[23] In his aesthetic phase, Rango exemplified this.

When Miss Beans carelessly announces to the town that the water bank is running dry, he quells the mob with a speech and gets the town back into a good mood without addressing the reason behind it. When the bank is robbed, he makes another speech. He repeats the words of the Mayor. The repetition is important.”[24] Kierkegaard believes that a society obsessed with reflection recycles slogans and buzzwords so well that individuality disappears. “Nowadays,” he worries, “it is possible actually to speak with people, and what they say is admittedly very sensible, and yet the conversation leaves the impression that one has been speaking with an anonymity… People’s remarks are so objective, so all-inclusive, that it is a matter of complete indifference who expresses them.”[25]

The words themselves, “we all know what to do,” are also important. Kierkegaard says that in our day, “everyone knows a great deal, we all know which way we ought to go and all the different ways we can go, but nobody is willing to move. Rango then rides out with a posse, not because he is convinced it will help, or even because he wants to help. “What do we do now, Sheriff?” Mr Furgus asks. “Now, we ride!” Later, Waffles ask the same question, and Rang answers the same. “We ride.” And so ride they do, through the desert. When Spoons asks over the thundering of ostriches’ feet, “where are we going?” Rango has silence for an answer. The ride is just a convenient ruse to fool the people into thinking they are doing something about it. Rango is fooling the people, but he does not know that he is also being fooled by the mayor. It is only after a fruitless chase, when he realises Miss Beans has been right all along about the mayor’s complicity, that we see the first glimpses of true conviction forming in Rango.

An Aside 2: Another Possibility is Destiny

Rango is an excellent film. Its engagement with the philosophy of identity and selfhood is not simplistic, and there is no room here to go through all the strands. Even the Kierkegaardian one has only been lightly explored. There may be entirely opposite perspectives running through as well. For example, there is a constant tension between predestination and free will. Does Rango become a hero in the desert? Or was he always a hero who just needed the right stage to show it? When Rattlesnake Jake looks him in the face that second time and dares him to pull the trigger, the two protagonists share a moment of subtle but profound mutual recognition. Rango says, “Try me,” and Rattlesnake Jake can see that he has it in him. Does Rango become the kind of person who has “killer in his eyes?” Or is it a deep layer peeled by the corroding effect of recent experiences? As many a romcom has asked, do people change, or are they incapable of it?

Soon after Rango’s fateful accident, Roadkill says, before pointing him to the desert, “destiny, she is kind to you.” And near the end of the story, the Spirit of the West says to him sarcastically, “That’s right. You came a long way to find something that isn’t out here. Don’t you see? It’s not about you. It’s about them.” The suggestion is that Rango was brought from his existence as a pet into the drama of Dirt to fulfil a purpose, a destiny. Rango’s declaration that he could not walk away from “his own story” is a rhetorical foil to a line spoken by the leader of the owls in the very beginning, announcing the tale of “a hero who has yet to enter his own story.” So the entire film can be read as the story of a lizard discovering and accepting his destiny, rather than creating it, in any way.

Yet, when Rango objects that he is not the hero he has been pretending to be, the Spirit of the West’s response is “Then be a hero,” as though it is entirely up to him. This duality of determinism and free will is characteristic not only of philosophical debate, but also of our own experience with everyday life. Determinism threatens from multiple sources—the laws of physics, of evolution, God, technology—while at the same time we live with an unshakable sense that we are beings with free choice.

Conclusion

Kierkegaard’s answer to who we are is that we will not know unless we go on a journey that begins with us hiding your deepest desires even from yourself, owning it, completely giving up on it, and then regaining it through the help of an outside power. This outside power can be anything that has a strong influence over you. For Kierkegaard, this is God, the Absolute. In short, you need pure, genuine inspiration to return to the quest of chasing your dream. This inspired version of you is your ideal self. It is a powerful idea, and no doubt we can all relate, either with the difficulty of finding that inspiration or of finding that great idea in the first place. How does one find that idea for which you are willing to live and die? The lucky ones are thrust unexpectedly into conflict, calamity, and chaos that gives them a cause. Kierkegaard, these are the lucky ones. The melancholy Dane, right? Thinking about the French Revolution, perhaps, he looks wistfully back on an age before modernity and says they had it. In our present age of reflection, however (see Aside 1), that is the rub. From TEDTalk to therapy, we are still floundering for an answer, riding ostriches aimlessly across the Mohave desert.

[9] Amir, 94.

[10] Amir, 95.

[11] Søren Kierkegaard, trans. Alistair Hannay, Fear and Trembling, Kindle edition (London: Penguin, 1985) 17.

[12] John Logan, Rango Screenplay.

[13] Kierkegaard, Fear and Trembling, 75.

[14] Kierkegaard, Sickness Unto Death, 39.

[15] Kierkegaard, YHWH stands for Yahweh, a Hebrew name for God.

[16] Kierkegaard, Fear and Trembling, 72.

[17] Kierkegaard, Sickness Unto Death, 82.

[18] Kierkegaard, Fear and Trembling, 72.

[19] Kierkegaard, Søren Kierkegaard, Journals and Papers. Ed. Edna H. Hong and Howard V. Hong, Assisted by Gregor Malantschuk, vols 1 & 2. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1967-78., 34.

[20] Kierkegaard, Fear and Trembling, 72.

[21] Kierkegaard, Fear and Trembling, 55–56.

[22] Søren Kierkegaard, Two Ages: The Age of Revolution and The Present Age, A Literary Review. Published as The Present Age: On the Death of Rebellion, edited by Alexander Dru. New York: HarperCollins, 1962., 3.

[23] IKC: TA – International Kierkegaard Commentary: Two Ages, edited by Robert L. Perkins. Macon: Mercer University Press, 1984. Chapters: Robert L. Perkins, “Introduction,” xiii-xxiv; Roberts C. Roberts, “Passion and Reflection,” 92.

[24] Kierkegaard, Two Ages, 53.

[25] Kierkegaard, Two Ages, 51–52.