The Lonely Lizard and the Melancholy Dane

Reader beware, spoilers abound.

Rango, the 2011 film written by John Logan, is a great movie. It is a about a lizard in search of his identity. Sure, the movie can be interpreted a few different ways: a story of the oppression of the poor by the powerful, the suppression of the masses by opiate of religion, the making and meaning of a hero. But for me, it is really about a question that haunts all of us at some point in our lives, the basic question of who we are.

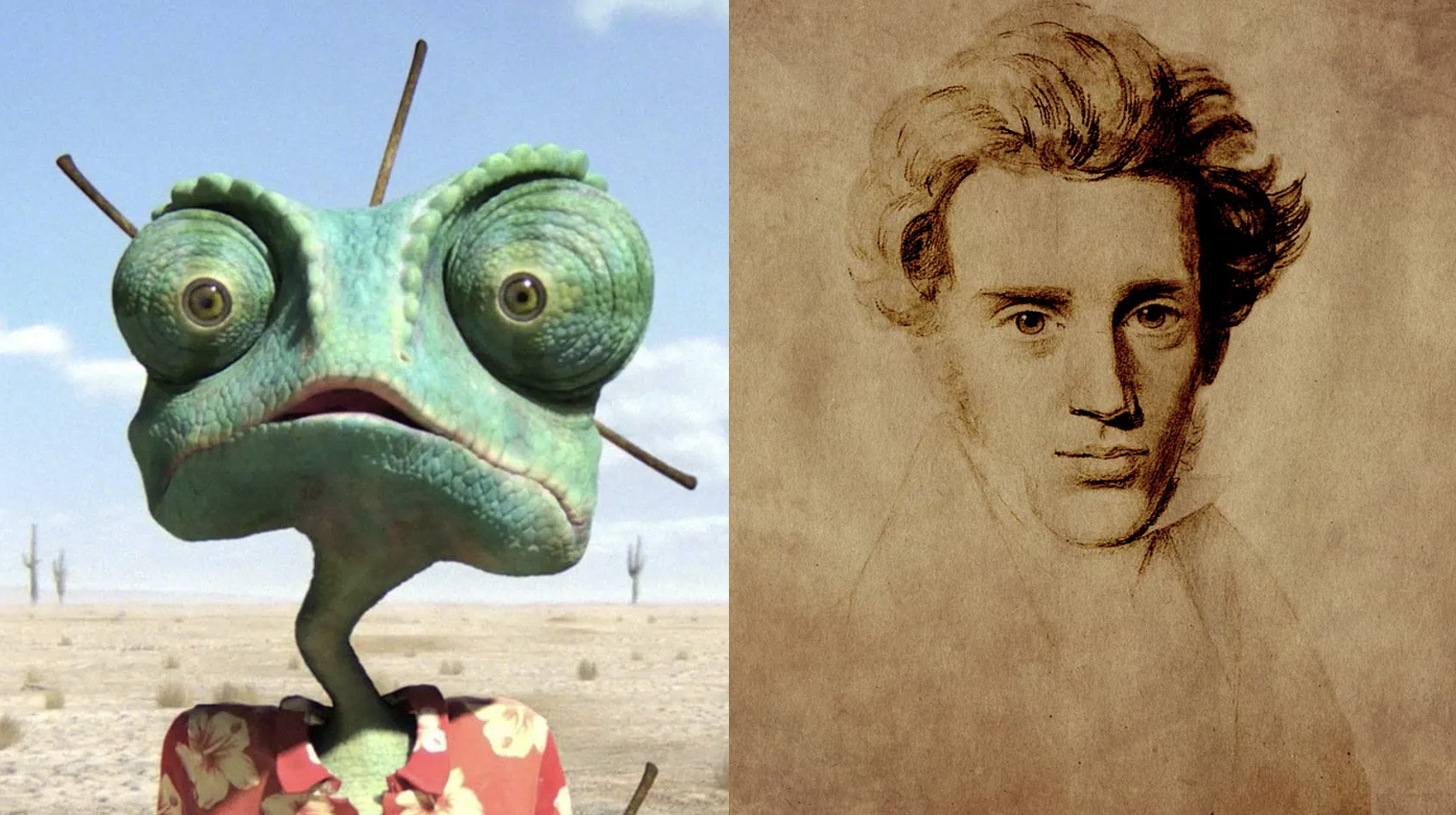

While thinking about the film recently, I could not help but notice how closely it follows the philosophy of the 19th century Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard. Perhaps no one has taken up this question as exhaustively and as eloquently as Kierkegaard has. Kierkegaard wrestles with the problem of the self and how it is to be found and known. His theory is a deeply personal, inwardly navigated quest that has earned him the title of the melancholy Dane. I studied Kierkegaard and the question of identity in the age of social media, so it is not surprising that I made the connection. Bias, sure, but trust me there’s something there.

There can be none more fitting conversation partner then, because Rango brings to cinematic life a picture of what this quest for our true selves can look like through the example of “a very lonely lizard.”[1]

Before getting into the weeds, Kierkegaard uses some terms that will be helpful to keep in mind. Anxiety in its more intense conscious form is despair. Infinitude or possibility is the main feature of the aesthetic realm. Necessity or finitude is the state in which one is grounded in a certain identity and way of life. In addition, it will help to take a quick tour through some of his main ideas in relation to this film. These are the stages of life, the dizziness of freedom, and the leap of faith.

Kierkegaard and the Stages of Life

Kierkegaard talks about three stages or spheres or personal existence. These “stages” are not necessarily steps on a process, they are more like styles of living that can coexist with each other, but that also have a relationship like a ranking scheme. The first is the aesthetic life, the realm in which a person lives for sensory experience. In this sphere of life, the person pursues pleasure and avoids pain. It is the stage of hedonistic exploration whose aim is to conquer boredom. The next one is the ethical sphere. Here, a person commits herself to the requirements and rules of the society, the family, the state, the religion, or whichever other institution holds influence in the social space in which the person lives. She does this believing that following the rules is the correct way to live. By “correct way,” I mean what Kierkegaard calls the limiting ideal of her life. She is looking for a principle of life that can provide an anchor on which she can rest. But the ethical sphere will not provide this, Kierkegaard says. The only true limiting ideal is to be found in the third sphere, the religious sphere. It is here where a person finally realises that life is not about following rules, but about entering a state in which, in the eyes of everyone else, she makes her own rules. What everyone else does not and will not see, is that she is really acting in harmony with a higher power whose presence she has entered. She is now, as the philosopher says, “resting transparently before God.” Kierkegaard uses Christian language, but his philosophy applies to any conception of the Absolute, another term he likes.

There are many ways to make this journey. The aesthetic person necessarily explores many ways of experiencing life. She reaches for the vastness of possibility, taking many different paths, both branching and parallel, to many different versions of herself. Kierkegaard calls this infinitude (also sometimes possibility), and its subjective principle is extensivity. That means, to explore our multiple possible selves, we must give ourselves to a way of learning the truth that relies on our experiencing these possibilities. It is about living out the dreams, in a way, to see what it is really like to be this way or that. It is a case of sensory or sensual immersion.

This does not really get us away from the aesthetic realm of things. To do that, we must retreat from infinitude into finitude, which he also calls necessity. The principle at play here is intensivity, and the practice of intensivity is solitude. It is easy to imagine here that Kierkegaard is calling for some kind of monastic or ascetic retreat from society. Far from it, he is calling for an internal movement of the mind. He is asking the individual to turn its thoughts inwards to her own mission, one’s own life purpose. This means we must come to realise what this purpose is. Fulfilling one’s purpose is hard, for sure, and Rango does not have it easy with Rattlesnake Jake and the Mayor of Dirt. But his journey is a journey of discovering his purpose, and it is infinitely more difficult. In this article, my goal is to show how the lizard’s journey is one we can all relate to, and hopefully learn from. Let’s get into it.

“A Man of Many Epithets”

When the movie begins, our lizard appears in what looks like a movie set. He is directing and acting in his own movie. His characters are inanimate, one of them is dead. Yet, he carries on with them as though they can understand his many prompts and instructions. He imagines being told by one of them that his character is undefined. The lizard rejects the criticism. “I know who I am… I’m the guy, the protagonist, the hero.” Even this early we begin to get a glimpse into his predicament. He is daydreaming as a way of escaping the gnawing agony of lacking a true sense of who he is. In reality, he is a pet chameleon in a glass box, kept with other props for the amusement of his owners. He does not want to accept this truth, however, and escapes it by imagining himself in many different worlds—sea captain with a mechanical arm, an anthropologist in the Congolese forest, a hairy chested, Spanish guitar-playing Casanova.

Before we even arrive at the town of Dirt, our lizard is asked three times, “Who are you?”

When he meets Miss Beans in the Mohave desert, she asks him “Who are you really??” He breaks into a self-eulogising monologue, “Well, I’m a man of many epithets. There’s my stage name, my pen name, and avatar, I used to have a pseudonym… I’m actually one of the few men with a maiden name!” The message is that this lizard has no idea of his true identity. He does not know who he is. But rather than admit this, he hides behind many possible identities. He is Kierkegaard’s aesthete. He is exploring multiple options for who he could be in the realm of the aesthetic, which is the realm of infinitude, or infinite possibility. Kierkegaard says this will not work, for

“the self runs away from itself in possibility, it has no necessity to which it is to return; this is possibility’s despair. This self becomes an abstract possibility; it flounders in possibility until exhausted but neither moves from the place where it is nor arrives any- where, for necessity is literally that place; to become oneself is literally a movement in that place.”[2]

What this lizard needs, is a way to limit possibility and ground himself in a single, necessary identity.

“A Town? With Real People?”

What is our friend seeking? In the beginning, it is certainly not the enlightenment proclaimed by an armadillo aptly named Roadkill. But our protagonist’s desires are more aesthetic. He is seeking the pleasure of company in society. In his daydreaming, he is a hero enjoying “the adulation of his numerous companions.” But then he makes a realisation. His character is undefined. What its needs is “an ironic, unexpected event, that will propel the hero into conflict.” It is telling that he announces this realisation as an epiphany, which in Christian theology can refer to a manifestation of divinity—if of God, a theophany, if Christ, a Christophany—to an unbeliever. Of course, this unexpected event happens in the form of a car accident that leaves him stranded on a desert road. He learns here from the run-over armadillo, himself seeking enlightenment, that the way to “what you seek” is in the desert, specifically in a little desert town called Dirt. The green chameleon has told Roadkill he is thirsty and looking for water. The armadillo understands the real need of this “lonely lizard.” Our friend is excited. “What-what-what, a town? You mean like, with real people?” all the while setting his imaginary hair. “If you want to find water,” says the wise armadillo, “you must first find dirt.” More metaphors. He might as well have said, “if you want to find the company of a town, you must first face solitude in a desert.”

“I’m Blending! I’m Blending!”

As soon as he is in the desert, as you might expect, “deserty” things start to happen. To escape a red-tailed hawk, he is advised to “blend in.” He tries, imitating a toad and a cactus. But the attempt causes anxiety. He can’t control his colour changes and they end up being more of a beacon than a camouflage.

After performing a dance for Miss Beans, she asks, “you ain’t from around here, are you?” His response, “I’m still working on it.” On the dance? Or on being from around here? When he arrives in Dirt, he is told “strangers don’t last long here.” His solution is to remind himself, “right, blend in.” He tries to emulate the walking styles and demeanours of the inhabitants. On entering the saloon, he drinks the cactus juice offered him even though it kills a fly in front of him. The chameleon here exemplifies that stage at which Kierkegaard would say most people spend their lives. He is a person trying to be normal, a person being ground into a uniform powder by society, rather than being ground into a definite shape by a higher ideal. Such a self abandons “being itself out of fear of men.”[3] Blending in, Kierkegaard warns, causes the individual to slowly loose herself in the desire to be normal:

“Surrounded by hordes of men, absorbed in all sorts of secular matters, more and more shrewd about the ways of the world-such a person forgets himself, forgets his name divinely understood, does not dare to believe in himself, finds it too hazardous to be himself and far easier and safer to be like the others, to become a copy, a number, a mass man.”[4]

The desire to blend in is suicide to the true self.

Inside the saloon, his blending in doesn’t quite work. He is confronted once more with the thematic question, “You’re a long way from home, aren’t you? who exactly are you?” This time, he actually pauses and considers the question with a poignant soliloquy. “Who am I? I could be anyone.” But this time his response is not like in the opening scene. He does not go off into a spiral of multiple imagined selves. He is not flippant. He is serious. What has changed? Kierkegaard’s answer is anxiety. Anxiety, when we are conscious of it, leads us to grapple seriously with who we really are and who we can be. Our companion, at this point, represents what Kierkegaard calls the ironist. This is the junction between the aesthetic and the ethical. The ironist “is a person who has become aware of an actual and an ideal self.”[5] The scales of delusion fall off and they must make a choice to enter the ethical or not. Sometimes this takes the form of a religious teaching or experience that leads to conversion into that religion; or it can be the process of naturalisation into a new citizenship. For the lizard, it was something of the latter, a chance to be “from around here.” In this scene, the play-acting genius comes into his own as Kierkegaard’s aesthetic poet. His eloquent fabrication of a life narrative is believable, and it initiates him for the first time into society.

“The Name’s Rango”

The lizard makes up an incredible story in which he is, as usual, an unassailable protagonist. The patrons of the saloon buy it, and he becomes Rango. After a series of incredible events, Rango is inducted as Sheriff of Dirt. This gets him a meeting with the mayor who hands him a sheriff’s badge, declaring, “your destiny awaits.” The plain, unlabelled badge clearly symbolises a blank slate. For Kierkegaard, destiny is not some predetermined fate; it is something created in the course of existing in transparent relation to God. The mayor says “control the water and you control everything.” The desert, then, is organised according to a principle of power. Many philosophers have discussed this, and in fact, power is what many people use to interpret social conditions today. And the mayor tries to control the people of Dirt through a regular set of rituals designed to affirm belief and hope in a better future “despite all evidence to the contrary.” An obvious Marxist analysis of social history is woven in which we will not go into. What is relevant here is that the mayor will soon find out his “immutable law” expresses an illusion of control. Soon after he appoints Rango as sheriff, the bank is robbed.

But before then, Rango enjoys a stint of fame and some fortune. He gets spa treatments, a host of attendants, access to the bank’s water, and, it seems, “the adulation of his numerous companions,” as he has desired from the beginning. He is living his dream, it would seem. Inhabiting this “Rango” persona he has created, our lizard appears to have grounded himself in one identity and become Kierkegaard’s single individual. But in reality, he is merely indulging one aspect of infinitude, an aspect Kierkegaard calls the fantastic, or as we would say, the fantastical.

“Infinitude’s despair, therefore, is the fantastic, the unlimited… The fantastic, of course, is most closely related to the imagination, but the imagination in turn is related to feeling, knowing, and willing; therefore a person can have imaginary feeling, knowing, and willing.”[6]

So, the lizard may think he is Rango, and he indeed seems to. In a later scene he says to the mayor, “I’m the law around these parts.” The mayor comments to his cronies after the lizard has left, “our new sheriff has been playing the hero for so long he’s actually starting to believe it.” In reality, Rango does not exist, it is an imaginary willing, that is, the performance of a dream that has not actually come true. And “as a rule, imagination is the medium for the process of infinitizing.”[7] Rango is a fantasy. “The fantastic,” Kierkegaard say, “is generally that which leads a person out into the infinite in such a way that it only leads him away from himself and thereby prevents him from coming back to himself.”[8] As long as our hero remains here, he will never truly find himself. Our hero needs something to jolt him out of this fantasy.

What might help? A cool feature of this movie is how it constantly rehashes themes from earlier scenes. Just as in the beginning the lizard determined that what he needed was something to propel him into conflict, here too, he needs a true challenge to wake him up. It comes when the bank is robbed and Rango vows to find and apprehend the culprits.

How does this propel Rango along his journey, and where does it lead? Find out in Part 2 – A Paradigm Shift

[1] Roadkill, Rango, 2011.

[2] Søren Kierkegaard, Sickness Unto Death: A Christian Psychological Exposition for Upbuilding and Awakening, edited by Edna H. Hong and Howard V. Hong. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013, 35-36

[3] Kierkegaard, Sickness Unto Death, 33.

[4] Kierkegaard, Sickness Unto Death 33, 34

[5] Lydia Amir, “Stages,” in Volume 15 Tome VI: Kierkegaard’s Concepts: Salvation to Writing, ed. J. Emmanuel, S.M., McDonald, W., & Stewart, 1st ed. (London: Routledge, 2015), 92

[6] Sickness Unto Death, 30-31.

[7] Kierkegaard, Sickness Unto Death, 30.

[8] Kierkegaard, Sickness Unto Death, 31.